Black carbon, also known as soot, is a visible pollutant that emanates from diesel engines or biomass burning in the form of black smoke and has major repercussions on both climate change and public health.

In this article, we analyse what black carbon is exactly, where it comes from, how it affects us and why it is important to monitor it in order to analyse what measures can be taken to effectively reduce its impact.

What exactly is black carbon (BC)?

According to the definition provided by the UNEP and the WMO, black carbon can be defined as an aerosol or solid particle suspended in the air that is formed through the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, wood and biomass.

All particle emissions from a combustion source are generally referred to as ‘particulate matter’ (PM) and are usually classified according to their size: less than 10 micrometres -PM10- or PM2.5 for those less than 2.5 micrometres (more information in our article on the Classification of Airborne Particles).

Black carbon is not a specific molecule or even a gas: it is an operational term that encompasses multiple compounds within the solid fraction of PM 2.5, whose most defining property is their ability to strongly absorb light and convert that energy into heat.

It is precisely this heat capacity that makes it a powerful agent of climate change.

Is black carbon the same as soot?

No. Although the terms ‘soot’ and ‘black carbon’ are often confused, there are differences in their origin, composition and risk profile.

In theory, if fuel were to burn completely, all of its carbon would be converted into carbon dioxide (CO2).

In practice, however, this type of combustion has been shown to be inefficient and, along with CO2, releases a mixture of gases and particles often referred to as ‘soot’.

Soot is a general term that refers to a complex mixture of particles and gases that is an unwanted by-product of incomplete combustion.

This soot is an amalgam that contains black carbon as one of its main components, but also includes organic carbon, ash, metals and organic compounds such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

According to the study made by Bond et al. (2013), black carbon is therefore a more specific term that refers to the fraction of soot that:

- Exists as an aggregate of small spheres

- Is refractory, with a vaporisation temperature close to 4000K

- Strongly absorbs visible light

- Is insoluble in water and common organic solvents

What health and environmental effects does black carbon have?

Black carbon has a dual harmful influence on the planet: on the one hand, it is a powerful climate warming agent and, at the same time, a serious risk to public health.

Climate impact of black carbon

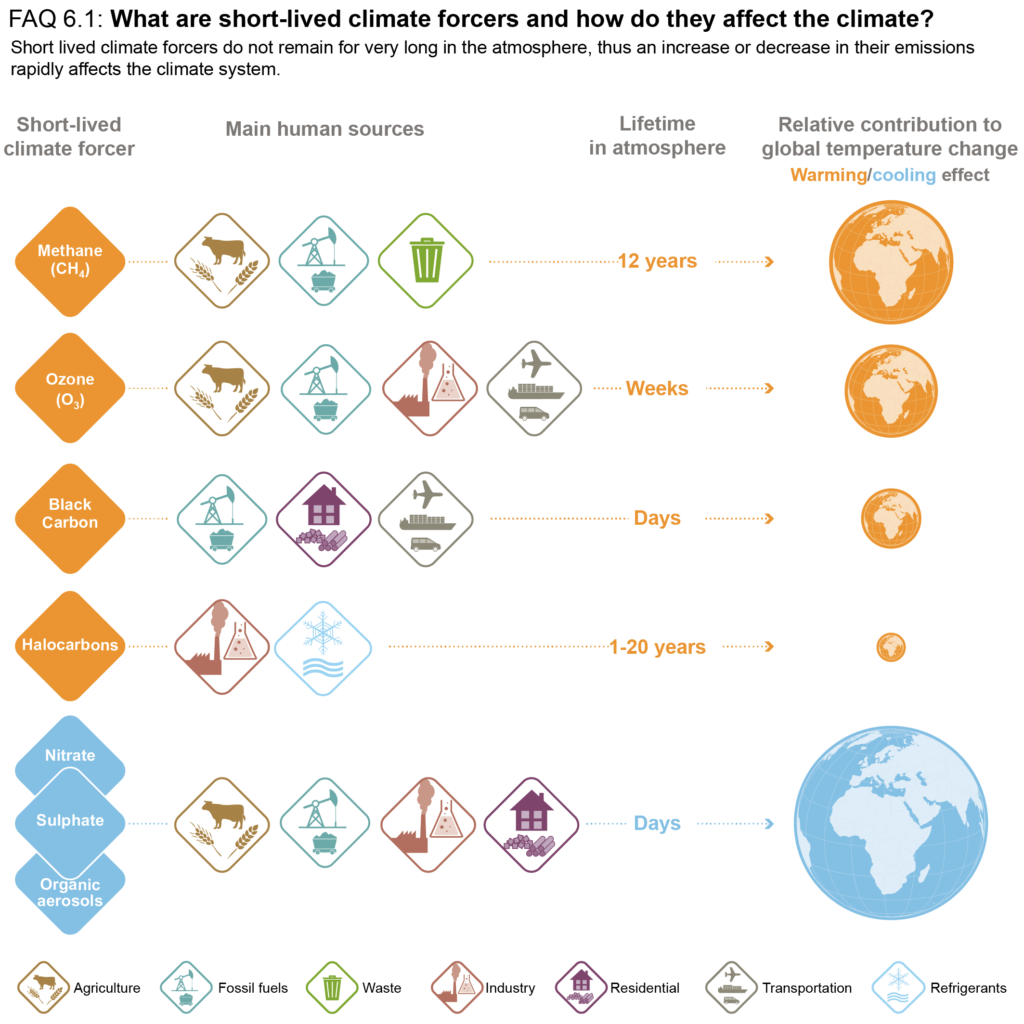

Black carbon belongs to a group of substances known as Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs).

These short-lived climate pollutants include black carbon (BC), methane (CH4), tropospheric ozone (O3) and hydrofluorocarbons (HCFs), and are considered the main contributors to anthropogenic global warming after carbon dioxide (CO2).

According to the CCAC, SLCPs are responsible for up to 45% of current global warming.

Source: FAQ 6.1 Figure 1 in IPCC, 2021: Chapter 6. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Instead of remaining for years or centuries like other greenhouse gases (CO2 can last between hundreds and thousands of years, while CH4 remains for around a decade), black carbon is quickly deposited outside the atmosphere through rain or gravity, remaining in the air for only between 4 and 12 days.

Comparative chart of the effects of BC and CO2 on global warming

| Feature | Black Carbon (BC) | Carbon Dioxide (CO2) |

| Type of Pollutant | Aerosol (solid particle) | Greenhouse Gas |

| Atmospheric Lifetime | Days to weeks (4–12 days) | Hundreds to thousands of years |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP at 20 years) | ~1,500 | 1 |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP over 100 years) | ~460 | 1 |

| Primary Warming Mechanism | Absorption of sunlight in the atmosphere and on surfaces | Trapping of infrared radiation (heat) emitted by the Earth |

| Geographical Impact | Highly regional and concentrated near sources | Globally well mixed |

| Benefits of Mitigation | Rapid (days to years) | Slow (decades to centuries) |

In summary, how does black carbon contribute to global warming?

- Direct radiative forcing: when black carbon particles are suspended in the atmosphere, they absorb energy from sunlight and release it in the form of heat, warming the surrounding air and surfaces in the regions where it is concentrated.

- Albedo reduction: When deposited on naturally white and bright surfaces such as ice or snow, it darkens them, decreasing their albedo (ability to reflect sunlight back into space) and causing a change in global temperature that directly affects the accelerated melting of the cryosphere.

- Disruption of the hydrological cycle: black carbon interacts with clouds, altering their formation, lifespan and reflectivity. These interactions disrupt regional precipitation patterns and can affect important weather patterns such as monsoons, which are essential for agriculture and livelihoods in Asia and Africa.

- Damage to vegetation: when deposited on plant leaves, it heats the surface and damages cells, inhibiting CO2 capture through photosynthesis.

- Appearance of “brown clouds”: in areas with high solar radiation, it is one of the main factors contributing to the so-called “brown clouds” that cover large regions, such as Asia.

Health effects of black carbon

Beyond its impact on the climate, black carbon is a serious air pollutant with significant consequences for human health.

As a major component of fine particulate matter or PM 2.5—whose aerodynamic diameter is less than 2.5 micrometres—it evades the natural defences of the respiratory system and penetrates deep into the pulmonary alveoli, from where it can pass into the bloodstream and be distributed throughout the body.

Figures suggest that around 4 million people die each year from prolonged exposure to this type of fine particulate matter

This health impact is geographically uneven. Populations living near major emission sources, such as busy roads or industrial areas, suffer much higher exposure.

However, the most serious problem at the individual level occurs in developing countries, where indoor air pollution is caused by the use of solid fuels (wood, coal, manure) in inefficient stoves.

In summary, what are the health impacts of black carbon?

- Strokes.

- Heart attacks.

- Chronic respiratory diseases such as bronchitis, aggravated asthma, and other cardiorespiratory symptoms.

- Lung cancer.

- Premature deaths in adults with heart and lung disease.

- Premature deaths in infants and children from lower respiratory tract infections (pneumonia).

- Problems with cognitive development in children.

What are the main sources of black carbon emissions?

It is essential to accurately identify the sources of black carbon emissions in order to design effective mitigation strategies.

These sources vary significantly by economic sector and geographical region, reflecting different levels of technological development, cultural practices and regulatory frameworks.

Classification of black carbon emissions by source

The main sources of emissions are related to incomplete combustion and can be either anthropogenic or natural.

Anthropogenic sources of black carbon are the result of human activity and cover a wide range of combustion processes, such as:

- Burning fossil fuels for transport, such as diesel or coal.

- Use of solid fuels and biofuels (wood, manure and agricultural waste) for residential and industrial uses.

- Large-scale open burning of biomass, related to the burning of agricultural and forestry waste.

The main natural source of black carbon is forest fires. Although they are a natural phenomenon, their frequency and intensity are increasing in many parts of the world due to climate change, which in turn increases BC emissions into the atmosphere, creating a dangerous feedback loop.

Sources of Black Carbon emissions by sector

Globally, anthropogenic black carbon emissions are distributed across several key sectors.

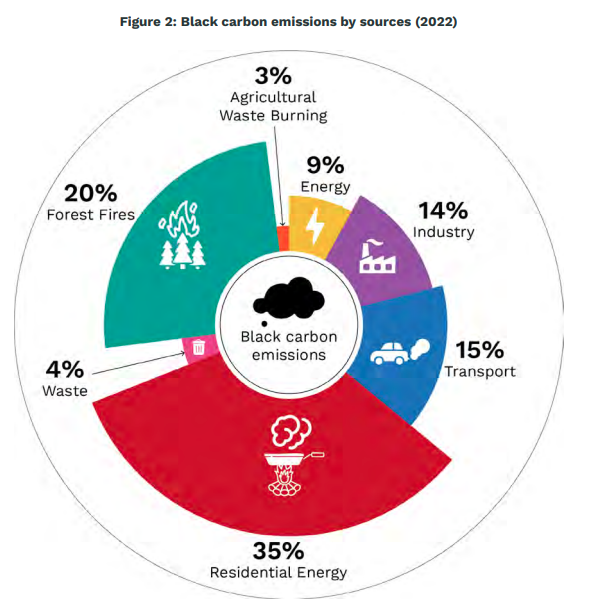

Source: Tackling Black Carbon: How to Unlock Fast Climate and Clean Air Benefits

Residential sector (domestic energy)

This is by far the largest contributor globally, responsible for approximately 35% of Black Carbon emissions in 2022, according to a report issued by the Carbon Containment Lab.

The main source is the use of solid fuels (wood, coal, agricultural waste, manure) and kerosene in inefficient stoves, ovens and lamps for cooking, heating homes and lighting, a common practice for billions of people in developing countries.

Transport

This is the second most important anthropogenic source, accounting for approximately 15% of global emissions. The main emitters within this sector are diesel engines, as this is usually an incomplete combustion process by nature.

This includes heavy vehicles (trucks, buses), agricultural and construction machinery, locomotives and, very significantly, maritime transport using heavy fuel oil, a particularly polluting fuel.

Emissions from maritime transport are particularly concerning in the Arctic, where deposited BC has an amplified warming effect.

Industry and energy production

These two sectors together contribute approximately 23% of global black carbon emissions. The most critical sources are industries that rely on high-temperature combustion processes, which often use outdated technologies.

This is the case for coke ovens, which are essential for steel production. Older models, known as ‘beehive’ ovens, are known for their dense BC emissions during charging, coking and unloading cycles.

Facilities that burn coal or heavy fuel oil to generate steam or electricity are also significant sources, although in developed countries they are often equipped with more advanced particle control technologies.

Furthermore, in many countries in Asia and Latin America, bricks are produced in artisanal or traditional kilns that are highly inefficient and burn highly polluting fuels such as low-quality coal, biomass and even plastic waste or tyres, releasing enormous amounts of black smoke.

Forest fires and open-air biomass burning

Forest fires are a massive source of black carbon, because combustion in a fire is inherently inefficient and largely dominated by the smouldering phase, which is what produces soot.

In addition, this sector includes agricultural practices such as the burning of stubble and crop residues to clear fields, or the burning of forests for deforestation and land conversion.

Why is it important to monitor and control black carbon?

Monitoring black carbon is essential for several strategic reasons that go beyond simply measuring pollution.

As a short-lived climate pollutant (SLCP) that, unlike CO2, which remains in the atmosphere for centuries, only lasts for days or weeks, reducing BC emissions has an almost immediate effect on slowing the rate of global warming.

Furthermore, black carbon is an almost exclusive tracer of incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biomass. Monitoring black carbon concentrations allows us to know, with almost complete certainty, whether its origin comes from:

- Diesel engines, especially in urban traffic

- Wood and biomass burning for residential heating

- Forest fires and agricultural burning

- Industrial activities with obsolete technologies or without emission control systems.

In this way, monitoring black carbon allows us to identify emission sources and verify climate mitigation measures in the short term.

At the European level, the importance of measuring and controlling black carbon has been recognised at the legislative level through the new European Air Quality Directive, adopted in April 2024, which for the first time requires Member States to measure black carbon at ‘super-sites’ for monitoring.

Conclusion: Black Carbon as a short-term target for improving health and climate

This pollutant, which comes mainly from transport, industry and domestic energy and is the result of the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels or biomass, forms part of the solid fraction of what we know as fine particulate matter or PM 2.5 particles.

Numerous studies have determined the harmful effects it has on both public health and the environment, as it is considered a short-lived climate pollutant (SLCP) with a high impact on climate change.

But if there is a positive side to all this, it is precisely the immediacy of its effects. For this reason, its reduction and control has become a short-term goal both in Europe, with the monitoring of black carbon at control Supersites, and globally.

Sources and References:

https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352615/9789289002653-eng.pdf?sequence=1

https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2013-12/documents/black-carbon-fact-sheet_0.pdf

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbono_negro

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-6/

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/short-lived-climate-pollutants-fast-climate-action

https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/BC_policy-relevant_summary_Final.pdf

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/faqs/IPCC_AR6_WGI_FAQ_Chapter_06.pdf

https://www.undrr.org/understanding-disaster-risk/terminology/hips/en0104

https://www.ccacoalition.org/es/short-lived-climate-pollutants/black-carbon